Introduction

Shoulder pain is a common and unfortunate occurrence. Even more unfortunate is the fact that many who suffer with daily shoulder pain think that it is something they have to accept as a normal part of life. Out of the significant portion of the population that deals with chronic shoulder pain, pain or injury of the rotator cuff is a prevalent issue. The current standard of care would lead many people to engage in physical therapy for rotator cuff injuries.

The rotator cuff is the name given to the group of muscles and tendons in the shoulder that are meant to keep the head of the humerus firmly anchored within the shoulder socket.

Common symptoms of rotator cuff injury include pain (ranging from a dull ache to sharp and stabbing), weakness and instability in the joint, clicking and popping, and muscle atrophy due to poor engagement.

When the rotator cuff is compromised, it is generally recommended that you avoid pushing motions, pulling motions, and overhead motions with the arms.

Physical therapy for rotator cuff pain is meant to re-stabilize the shoulder, reduce pain, and restore proper functionality of the shoulder.

When rotator cuff pain doesn’t improve with physical therapy, steroid injections and different types of surgery are often used next (1).

In this article we are going to briefly analyze rotator cuff physical therapy exercises and an alternative way to view rotator cuff health.

What Are Typical Causes of Rotator Cuff Pain?

According to the Mayo Clinic, rotator cuff injuries most often develop over time through repetitive overhead motions that inflame and damage the tendons. In less common cases, the rotator cuff is injured through blunt force trauma like falling or getting in an accident.

Other contributors to rotator cuff pain include:

- Age-related degeneration (which is likely actually a mechanical efficiency problem - as the next three bullets suggest)

- Poor posture

- Poor mechanics of the shoulder

- Muscle imbalances

- Genetic predisposition towards weak tendons

Rotator cuff physical therapy is aimed at strengthening the muscles that hold the humerus in the shoulder socket in hopes that this will reduce wear and inflammation on the shoulder.

What we hope to illuminate in this article, however, is that these exercises do not fully address what are perhaps the most important contributors to rotator cuff injury - poor posture, poor mechanics of the shoulder, and muscle imbalances.

While it is easy to make a generalized statement about how all rotator cuff injury or pain comes from “overuse”, there are many cases in which people use their shoulders much more than the average person with no problems throughout their lives.

While it is possible that some of these cases are due to a genetic predisposition to weak tendons - it is much more likely that those who have excellent shoulder health and longevity tend to use their shoulders in a way that is more mechanically efficient.

Could it be that the specific way the shoulder is being used mechanically actually has way more influence over its health than any other factor? What if we knew an ideal way to use the shoulder that only made it stronger over time while providing rotator cuff pain relief?

In a moment, we will discuss what evolutionary evidence suggests about what the shoulders primary functions are and what this means about how we should be training and rehabbing the shoulders.

First, let’s further break down the traditional view on shoulder rehab.

What Exercises Should You Avoid With A Rotator Cuff Injury?

Common exercises recommended to be avoided with a rotator cuff injury include:

- Overhead Presses

- Pull-ups and Chin-Ups

- Bench Press

- Upright Rows

- Lateral Delt Raises

- Push-Ups or Planks

- Shoulder Stretching

The more generalized recommendation is to avoid pushing, pulling, and overhead motions - especially overhead motions that bring the arm behind the head.

It is also commonly recommended to avoid any exercise that pulls the shoulders down such as deadlifts, back squats, and shrugs.

While it is certainly a good idea to rest an injury for a period of time in order to help it heal, the functions of the shoulder must be retrained at some point.

If we can acknowledge that posture, shoulder mechanics, and muscle imbalances can all influence your likelihood of developing rotator cuff pain - then we should consider these factors very carefully in our shoulder recovery process.

Furthermore, we should be asking ourselves what ideal posture and shoulder mechanics actually would look like in order to better inform our approach towards rotator cuff pain relief.

Next, we are going to take a look at some common rotator cuff physical therapy exercises.

What Does Rotator Cuff Physical Therapy Normally Look Like?

A typical protocol of physical therapy for rotator cuff pain lasts about 4 to 6 weeks with a general recommendation to continue exercises weekly for life-long shoulder health.

Common rotator cuff physical therapy exercises include:

Pendulums: This exercise consists of placing your body in a hinged position, placing one hand on a ledge for support, and hanging the opposite arm towards the floor while rotating it in circles.

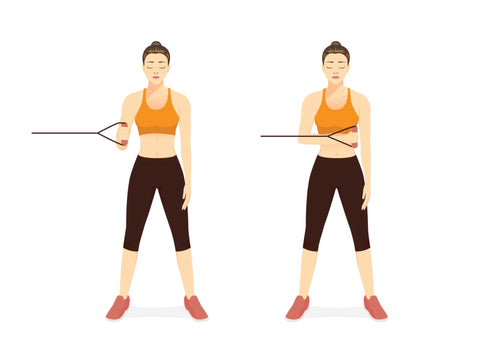

Loaded Internal Rotation: This exercise involves holding a weight or resistance band with your arm at your side and a 90 degree bend in the elbow. While doing this, you internally rotate the humerus bone - reaching your hand across your midline.

Loaded External Rotation: This exercise involves holding a weight or resistance band with your arm at your side and a 90 degree bend in the elbow. While doing this, you externally rotate the humerus - reaching your hand away from your midline.

Shoulder Retractions: This involves pinching the shoulder blades back several times in a row.

Rows: This typically involves holding on to resistance with both hands and pulling both arms back, squeezing the shoulder blades together at the end of each rep.

Some rotator cuff physical therapy protocols also involve different variations of the above exercises and sometimes different forms of stretching.

While the typical rotator cuff physical therapy exercises are well-intentioned. They tend to overlook one majorly important principle of how the shoulder is meant to work - integration.

The Major Shortcoming of Rotator Cuff Physical Therapy Exercises - Lack of Integration

Rotator cuff physical therapy exercises don’t take into account the integrated function of the shoulder in relation to the rest of the body.

What if the reason your shoulder is bothering you is because it is adapting to poor positioning of the ribcage? What if that poor positioning of the rib cage is related to the way you have trained your abdominal muscles to work?

The entire body is connected intricately through the myofascial system and nothing on the body can be truly treated in isolation.

Read more about how integrated training is superior here

When we look to our evolutionary past, there is a large amount of evidence that the human shoulder adapted for the primary function of running and throwing (2). In fact, it was likely our ability to run and throw with precision that allowed us to dominate the earth the way we have.

The specific anatomy and capabilities of the human shoulder, along with the rest of our human anatomy, was likely developed through very specific environmental pressures.

This means that our muscles were literally driven into existence to allow us to do things like run and throw. While this evolutionary theory is highly supported by evolutionary paleobiology, there is still a lack of application when it comes to our fitness and rehabilitation practices.

It is likely that if we look at the muscle activation and range of motion that occurs during running and throwing, then we will have the code for how to train the shoulder for optimal function.

Considering this, we can observe that the shoulder operates with the entire body. In running and throwing, there are contractions that must occur in several parts of the body simultaneously in order to allow ideal ranges of motion to be achieved in places like the hips and shoulders.

This means that if we are truly going to prepare the body to resist pain and injury, we must take into account the motions that created our muscles in the first place.

By designing exercises that account for the functions our shoulders were adapted for, we can target each muscle in the ideal manner.

For more information on the shoulder, check out this article:

Shoulder Mobility: What is Good Shoulder Posture?

To dive deeper on the subject of what our evolution tells us about achieving ideal fitness, check out this article:

What is Functional Strength Training?

Is It Possible to Rehab a Rotator Cuff at Home?

Considering what we’ve discussed so far in this article, improving your biomechanics is likely a more viable solution than rotator cuff physical therapy exercises.

By taking a more informed and precise approach with your rehabilitation, you can not only rehabilitate a nagging shoulder pain, but you can build strength that will prevent pain and injury in the future.

While improving your biomechanics can seem intimidating and highly technical, we’ve designed our 10-Week Online Course to allow anyone to begin addressing their biomechanics at home.

The 10-Week Course contains all the most fundamental techniques to start reintegrating your movement so you can feel more athletic while melting pain away. By addressing the entire system of your body, you can improve your movement and, in extension, achieve rotator cuff pain relief.

Sources

- Mayo Clinic: Rotator Cuff Injury

- Longman DP, Wells JCK, Stock JT. Human athletic paleobiology; using sport as a model to investigate human evolutionary adaptation. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2020 May;171 Suppl 70(Suppl 70):42-59. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23992. Epub 2020 Jan 20. PMID: 31957878; PMCID: PMC7217212.