There are a number of goals typically aimed for by the average person engaging in an exercise program. Some examples of these include:

- To improve “general strength” or to increase the strength of a certain movement (back squat, bench press, overhead press, etc)

- To improve range of motion in a movement or a particular joint

- To increase cardiovascular endurance or ability to sustain a heightened muscular demand over a longer amount of time

- To improve the aesthetic look of the human frame (to look more defined or athletic)

- To rehabilitate an injury

- To reduce pain within the body

- To improve performance in a sport (sport-specific training)

- To improve the ability to perform everyday activities

These are all perfectly reasonable motivations for engaging in physical activity and humans should certainly look to improve their quality of life through training.

In this article we are going to discuss the concept of isolated muscle training, compare it to integrated muscle training, and make an argument for which approach should be prioritized in order to create maximum improvements in quality of life.

First, We Should Consider How Muscles Formed on the Body

When we look to our evolution as a species, or even evolution as a general concept, we must consider environmental pressure and its influence on biological adaptations.

The glute max muscle, for example, is a muscle that developed fairly recently in our evolutionary history as humans. What was the stimulus that lead to its development?

When we think about the development of the glute max, it is highly unlikely that the glute developed as a result of choice. In other words, we did not simply decide to have glute max muscles.

It was more likely developed as a result of an environmental pressure requiring the human organism to be able to move in a certain way to ensure survival.

Anthropological evidence overwhelmingly suggests that standing, walking, running, and throwing are the defining movements of humans. Perhaps it was the refining of these movements which lead to the development of the glute max? After all, the glute max is largely involved in these movements.

If this is how the development of the glute max was stimulated, then this tells us that muscles developed around the necessity to perform integrated movements such as running and throwing.

If this theory were true, what clues would this give us in terms of how we should be training the human body for maximum benefit? What benefits should we see if our training is done in a way that actually takes our human blueprint into account?

If We Train the Human Body in a Way that Is Consistent with its Evolution, What Should the Results Look Like?

Considering the above, it seems that standing, walking, running, and throwing are primary movements for humans. This would also suggest that all other movements are secondary to these movements. This may also mean that a more effective training program may revolve around these functions whether it is aimed at improving strength, muscle mass, endurance, increasing mobility, or reducing pain.

Of course this hypothesis needs rigorous testing and this is what we have been aiming to do at Functional Patterns for over a decade. This is why we prioritize showcasing before and after results on real people that engage in our training.

Modern day fitness has become a bit abstract. Not only can we not agree upon what a good training program really looks like, but the majority of trainers don’t really seem to be concerned with recording and displaying the results obtained through their methods outside of a controlled study.

If they do showcase results, it is often in relation to a very limited set of parameters such as muscle gain, fat loss, or an improvement in a single lifting exercise. The question we ask ourselves at FP is if those improvements are coming at the cost of some other aspect of health.

If we are to advance as a society, and this goes for every field of study ever, we must test our assertions through the recording and assessment of results in real life and we must see how they pan out over time. How do we apply this to fitness?

Well, traditionally there are a few metrics by which people gauge their fitness levels. These include:

- Muscular and cardiovascular endurance

- Muscular strength

- And Mobility

Sometimes people have other goals, but for the general majority of people engaging in exercise, the above covers most of the motivation behind their training.

Now, if we are considering the evolutionary history of humans and we are trying to determine the more ideal way to train a human body, then what other benefits might we see from training?

We propose that the following would likely be seen:

- Higher running speed

- Better standing posture – running faster and more symmetrically should equate to a more upright and symmetrical standing posture

- Greater ability to build and retain muscle mass – muscles are being used the way they are designed

- Improved mobility without creating hypermobility in the joints – the body is only conditioned to operate in ranges of motion that are necessary

- Less joint pain – moving the body in the way it is designed would likely put less strain on joints

- Greater muscular strength – in scenarios that translate to everyday life

- Greater endurance – if the body moves more efficiently, the same movements become easier to sustain over time

While some may try to combine multiple fitness modalities together to achieve a wide range of effects, we make the argument that if you are actually training your body in a way that is specific enough to what it is adapted to do, then you should be able to achieve all of these attributes of fitness with only a small set of well-executed exercises.

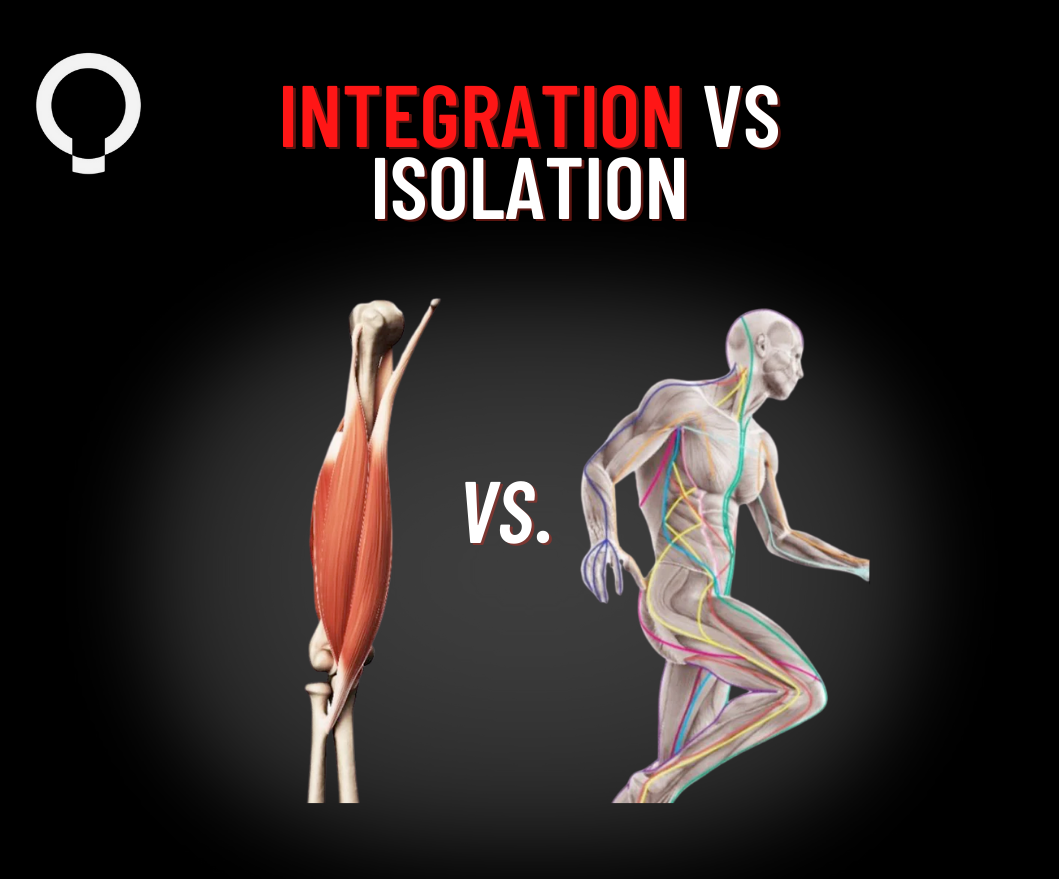

Training Isolated Muscles Vs Training Integrated Myofascial Chains

If muscles developed in relation to the integrated movements of walking, running, and throwing, then training in relation to these functions would likely provide the most benefits to the human body. This is a major hypothesis that we have been testing for over a decade.

If you are going to train the body in relation to its primary movements, there should be no isolated contractions. It is the specificity in which your muscles contract in relation to other muscles that determines the quality of your movement. This is the difference between a high-level athlete and someone who is in chronic pain with movement limitations.

The more isolated you become with your muscle contractions in a training setting, the less carryover there will likely be into everything else you do.

Without further elaborating on the theories of why one may be better than the other, let’s simply discuss the results that have come out of a more integrative approach to training.

On our results page you will find people of all ages and all ability levels. You will see people who have increased their running speed, reversed their chronic pain, and built muscle mass. You will see obvious improvements in standing posture and countless testimonials on the mental benefits of training in a more integrated way. These are very different people, all over the world, who have very different lives – but are engaging in the same training system and achieving similar results.

While we do not claim to have figured everything out when it comes to human movement, we do think we have substantial evidence to show that an integrative approach to exercise is highly beneficial for humans.

A Concluding Thought Experiment

After reading the content of this article so far, we want to leave you with some questions to consider:

Operating on a spectrum, should we aim to make muscles fire in a more integrated manner or a lessintegrated manner? In your training, are you considering which direction on the spectrum you are adapting your body? What are the long-term ramifications of adopting each approach?

We hope this article and thought experiment serve you well on your path to optimal health.